|

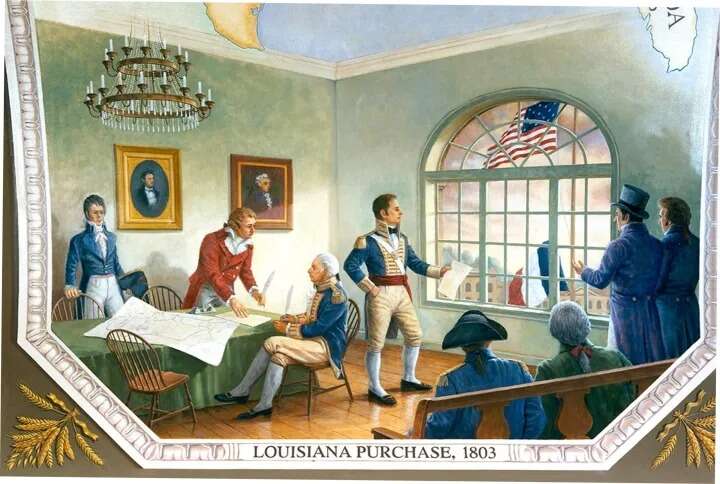

Louisiana’s Anglo-American population traces its ancestry to five major immigrant groups. The first large wave of Anglo-American immigrants reached Louisiana via New Orleans in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase (1803). These immigrants, drawn primarily from East Coast cities and New England, were primarily merchants and professionals who sought to capitalize upon the Crescent City’s burgeoning economy. The second and third waves of immigration arrived concurrently between 1820 and 1860. The larger of the two movements included individuals migrating across the Deep South, a migration ultimately terminating in Texas. In Louisiana, many of these westward migrants put down roots in Central and North Louisiana. The smaller antebellum influx consisted of wealthy individuals from the Tidewater districts of Virginia and the Carolinas. Many of the latter immigrants brought up small farms along the Mississippi River and other Louisiana waterways and consolidated them into large plantations. The fourth wave of Anglo-American immigrants arrived in the late nineteenth century, when thousands of Midwesterners (particularly Iowans) migrated to the southwestern Louisiana prairies and helped establish the region’s rice industry. The final Anglo-American influx occurred in the twentieth century, when Louisiana’s vast petroleum resources attracted thousands of oil field workers from neighboring states, particularly Texas and Oklahoma. While Louisiana began as a French colony and its dominant culture remained Creole French well into the nineteenth century, Anglo-Americans began to form a significant minority in the region in the late colonial period. After 1803, when the Louisiana Purchase added the colony to the United States, Anglo-Americans began arriving in rapidly increasing numbers, lured by ambition, cheap land, and government posts in the new territorial regime. The ensuing tensions between Creoles and Anglo-Americans, though sometimes exaggerated, played an important part in the social development of early Louisiana. The term “Anglo-American” was used primarily in the late colonial and early national periods (1790–1830) by French-speaking Louisianans to describe English-speaking newcomers—especially those from the United States. English speakers from England, Scotland, and Ireland might also be classified as Anglo-Americans, especially if they became US citizens and sided, as most did, with the American faction in New Orleans. Those newcomers born in the United States were commonly called “Native Americans” (not to be confused with indigenous Indians). In practice those described as Anglo-Americans tended to be of elite status. The term was not usually applied to the working-class sailors and boatmen who migrated to New Orleans (and who were more often labeled “Kaintocks”). While it might be applied to settlers in upcountry parishes like Ouachita and Concordia, it was most often used to describe the professional and mercantile arrivistes of territorial New Orleans—men who came to make fortunes in Louisiana as merchants, land speculators, and lawyers. |

|

A few prominent Anglo Americans in Louisiana: Daniel Clark, the first Delegate from the Territory of Orleans to the United States House of Representatives was born in Sligo, Ireland and arrived in New Orleans in 1786. Among other endeavors, Clark speculated heavily in land. William Charles Cole Claiborne was the first territorial and state governor of Louisiana, presiding over the region in its transitional years of Americanization from the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 to statehood in 1812. Wade Hampton (1752 – February 4, 1835) was a South Carolina soldier, politician, two-term U.S. Congressman, and wealthy plantation owner. Hampton served in the American Revolution, and in the U.S. Army. He was promoted to brigadier general in 1809, replacing James Wilkinson as the general in charge of New Orleans. Thereafter, he acquired a large fortune acquiring Louisiana Sugar plantations. At his death it was told that he was the wealthiest planter in the United States, owning nearly 2,000 slaves. |

|